Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Abel Meeropol (1939)

May 1911 – the lynching of Laura Nelson.

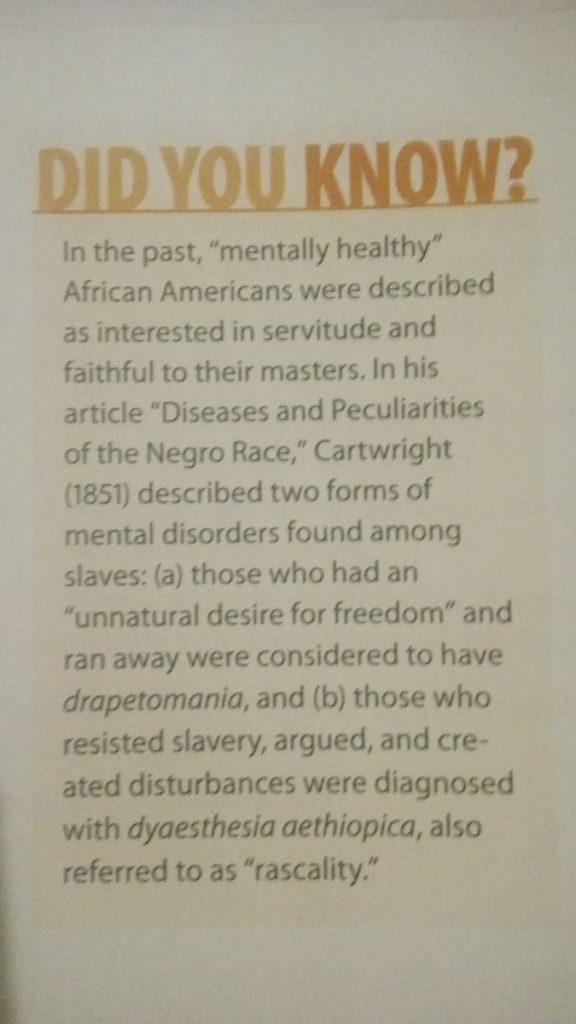

As in horror we watch the digital broadcast of beheadings conducted by ISIS, perhaps refusing to enter this raw confrontation with the blood of death, defeat and barbarity, we often hear that this is a throwback from the Middle Ages. Perhaps the easiness in believing that belies a deeper trauma, hidden in the dark night of our collective unconscious. To many African Americans, the word “lynch” is far from historic. To millions of free humans living under oppressive regimes across the world, it even remains a perpetual threat. Sexual transgression, the accusation of intention to commit a terrorist act (by carrying a pocket knife), racial difference, jealousy and poverty, all feed the atmosphere of the lynch. This is a dimension of material and spiritual poverty through which the most bloody and crowd-endorsed expressions of hatred and cruelty take form. The collective murder expressed through lynchings takes the form of racial discrimination, and America’s over 5000 lynch victims have included civil rights activists, Mexicans, Chinese, Indians and others as well as the vast majority of African Americans murdered for a perceived offence to white privilege.

It’s not a private fear – the fear to be lynched. It has within it the contractions of ultimate rejection, disenfranchisement, power abuse and social condemnation. Often, our worst nightmare is not to be the victim but to be identified with the perpetration. In the words of Theodore Roosevelt in 1903, anyone who witnesses or takes part in a lynch is going to carry the open wound of the trauma:

All thoughtful men…must feel the gravest alarm over the growth of lynching in this country, and especially over the peculiarly hideous forms so often taken by mob violence when colored men are the victims – on which occasions the mob seems to lay more weight, not on the crime but on the color of the criminal…There are certain hideous sights which when once seen can never be wholly erased from the mental retina. The mere fact of having seen them implies degradation…Whoever in any part of our country has ever taken part in lawlessly putting to death a criminal by the dreadful torture of fire must forever after have the awful spectacle of his own handiwork seared into his brain and soul. He can never again be the same man.

Scientists have now been able to trace the epigenetic tags – stressors affecting the DNA and signalling fight, freeze and flight responses to the body – within African American populations living today, tracing the population movements into North America, and out of the Southern states of the USA (as a result of lynching, intimidation and segregation laws). This is the science of epigenetics – the more refined layer above the DNA, that masterminds gene activation and gene suppression. Today coined “Post-traumatic Slave Syndrome”, the psycho-cultural inquiry into the damage done to all sides is finally emerging, endorsed by the evidence of genetic science. (See: Tales of African-American History Found in DNA, New York Times, May 27th, 2016)

The science of epigenetics is revealing how the external environment affects us at the molecular level by altering gene expression and function that can, in turn, be inherited. It refers to chemical modifications or “tags” that mark specific genes around the intricate DNA complex.

The science of epigenetics is revealing how the external environment affects us at the molecular level by altering gene expression and function that can, in turn, be inherited. It refers to chemical modifications or “tags” that mark specific genes around the intricate DNA complex.

From a psychological and healing perspective, the evolution of science and more sophisticated tools of inquiry into the nano-dimensions are literally showing us how our personality (that which makes us fearful, bad, good, guilty, a winner or a loser) is resonantly encoded in the form of stress responses around our DNA, and was received by us from our parents together with the cells of our bodies. This coding is formed by trauma and contracted states, or areas of stress and suffering. Healing is possible, when we are able to find peace with what was inherited, and create the inner safety for the genes to return to expression more directly attuned to the real-time environment.

The aim of the lynch – beyond the stolen rush of the immediate blood-fest of cruelty, lawlessness and the temporary proof that ‘might is right’ – is to spread terror through the grasping of God-like authority over dignity, life and death. An effect of this is learned helplessness, cooperation with systems of disenfranchisement and structures of subordination based on the basic, physical instinct to survive.

Moving with the power of raw emotion outside the structures of law, the vigilanti literally aims to extinguish the forms he or she fears, as embodied in the lynch victim. In the Southern States, this propagation of terror went viral in the form of postcards of lynch victims. According to TIME Magazine: “Even the Nazis did not stoop to selling souvenirs of Auschwitz, but lynching scenes became a burgeoning subdepartment of the postcard industry. By 1908, the trade had grown so large, and the practice of sending postcards featuring the victims of mob murderers had become so repugnant, that the U.S. Postmaster General banned the cards from the mails.” To any African American (and non African Americans), even such an image of racial crucifixion could be enough to awaken the terror embedded in the raw extinct to survive. Now, science has shown that those genetic alarm bells pass through the body from parent to child. Of course, when the world is unsafe for some, the world becomes unsafe for all: every perpetrator also embodies the terror that next time, he or she could be on the other side of the rope.

When Mark Wolynn wrote the book It Didn’t Start With You, he didn’t feel he yet had the authority of direct experience to write about the tremendous collective and individual trauma of slavery and the ongoing abuse of power within the racial divide within the USA. Then he met April, who’s healing journey unveiled one of the most brutal and unspoken chapters of America’s history.

The following is a special extract of April’s story, which is one of the second edition additions to Mark’s book: It Didn’t Start With You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who You Are and How to End the Cycle.

April, an African American quilt maker, was in her early forties when she saw a photo taken in 1911 of a black woman and her son hanging by their necks from a bridge. Several white men, women, and children lined the causeway above them. In that moment, April’s life changed. She became overwhelmed with the thought and image of lynching. “I couldn’t stop crying,” she said. “That could have been me and my son.” From the day she saw that photograph, April’s anxiety increased. “It was as though every tree I saw had a body hanging from it.”

I asked her if she knew of anyone in her family who had been lynched.

It was difficult to say. In the late 1800s, her grandfather, the child of a black man and white woman, was left, along with his sister, on the side of the road. Her family took in the grandfather, but not his sister. It’s unknown what happened to the grandfather’s sister or his father.

As we know from history, black men were often punished for having sexual relationships with white women. Yet, white slave owners routinely fathered children with the women they held captive. A study published in May 2016 found genetic evidence of this history buried in the DNA of African Americans alive today. The DNA bore traces of European descent, which could be time-stamped during the era of slavery, thus enabling researchers to validate what has long been common knowledge.

Although April couldn’t pinpoint with certainty that her grandfather’s father or sister, or anyone else in her family, had been hanged, she suspected someone had. At the very least, she carried the residues of a collective trauma, and shared it with other African Americans who felt similar fear.

April felt compelled to research every documented case of African American men, women, and children who had been lynched in America from 1865 to 1965. She uncovered the names of more than 5,000 people and sewed each one with gold silk thread onto a black quilt. With each name she added, April had a sense that another soul could finally rest. After three years, the length of time it took to finish the quilt, which now weighed twelve pounds, April finally felt free.

In Nondual Therapy, we emphasize that often the complete release of trauma involves awakening to the most unspoken feelings within the shared atmosphere of the event. In our determination to support – and identify with – the victim within ourselves, this often leaves the perpetrator unprocessed. The horrific, socially affirmed phenomena of lynching has impact on us all, as the trauma of rejection and condemnation takes on hellish proportions with an outcome of death. No-one, whether victim or perpetrator is genetically left untouched by being in this field, and we are all also in it. We needn’t warn that history repeats, as history is repeating as this is written, even within our collective dread of that repetition. It is an individual and collective responsibility to find and open an inner power that is deeper and unconditioned by the dynamics of victim and perpetrator. Out of this power, a deeper evolution that arises out of the freedom beneath all human differentiation can be liberated.

For online mentoring with Georgi to release the suffering of PTSD through Nondual Therapy, Find out more here.