WHO DO I THINK I AM?

Where would an individual begin to define where he or she begins and where he or she ends?

During the five decades I have been around this female physical body, I have carried many diverse ‘persons’ – forms composed from patchworks of feeling attachments and identification. No form of person has been able to last long. Whether by destiny, choice or accident, these years have defied the forms of conformity, convention, nationality, religion, culture, class, family and even at times, gender. The death or explosion of each form, birthed the emergence of the next. Behind these accelerated processes of transformation, I have been the only continuum – as one beyond time and beyond space, yet present within every time and space, unaffected, as if nothing ever happened. This one is present in all form, just as a dreamer is present in a dream. The dreams begin and end, but the dreamer remains.

Yet we can describe some of the persons I have thought I am. Such is life, a diving repeatedly into the sea of attachment, entanglement and identification and dying within it to find in the breakage and the end of personhood, that no one actually ever moved. Nothing happened. Just an illusion of personhood, intoxicating for a while, yet breaking open in conscious, eternal light or melting into warm, infinite darkness of home before birthing the next illusion. An illusion of personhood which is a strange kind of real-life dream with the appearance of high stakes. These illusions are born, take form, transform and die. A deeper continuity of featureless self remains.

Yet we can describe some of the persons I have thought I am. Such is life, a diving repeatedly into the sea of attachment, entanglement and identification and dying within it to find in the breakage and the end of personhood, that no one actually ever moved. Nothing happened. Just an illusion of personhood, intoxicating for a while, yet breaking open in conscious, eternal light or melting into warm, infinite darkness of home before birthing the next illusion. An illusion of personhood which is a strange kind of real-life dream with the appearance of high stakes. These illusions are born, take form, transform and die. A deeper continuity of featureless self remains.

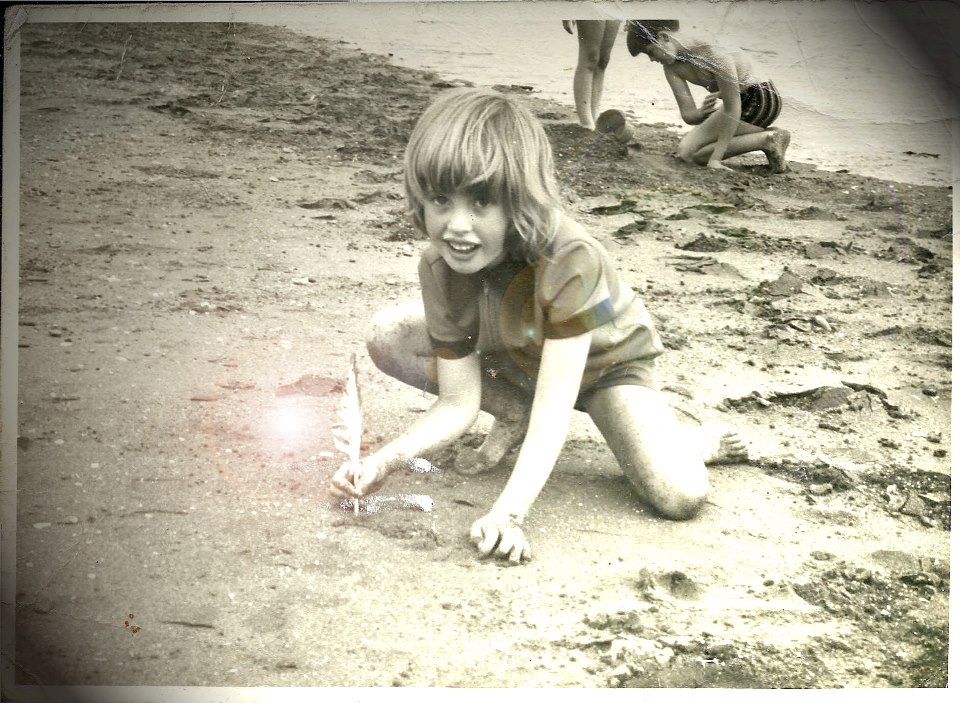

I was born in a small terraced house on a hill overlooking the steelworks of industrial Sheffield in Yorkshire, England in the early autumn of 1967. I heard the midwife burned the placenta on the fire and it made a very bad smell. The story stays as an imprint: the contrasting odours of new birth and the cremation of human flesh. Endings and beginnings. Creation and destruction, turning in a cycle of duality.

At that time, the geography of the planet was itself shifting. Jerusalem and territories all the way to Jordan River had been claimed by the young State of Israel in the 6 Day War, and for the first time in millennia, the world witnessed again a form which could be considered a Jewish Jerusalem.

I’m already building stories, when what was there for the new-born entity of form, was atmosphere: a responsive sense of care towards my parents and brother; with a subtle distress around the stress in the place where I had arrived. Only not to make it worse than my being here seems to make it. This was there, and is still there now, like a subtle mist at the portals through which personhood takes form, again and again

From that working class home infused with the stress of survival on little more than my father’s student grant, the family moved when I was three months old to Northamptonshire, where my father had got a job.

An early conscious memory was of consciousness itself. I was two years old, and had been put in bed (I imagine to take a nap) by my mother.

I lay on the white sheets, not sure what to do. I was aware that my legs were short, hardly reaching beyond the pillow, child’s legs, and I marveled how they had grown, because before they had been shorter. I gazed loosely towards the window where the afternoon sunlight was reflected in brilliance and shadow through the nylon, imitation lace curtain. Downstairs, I could hear my mother banging pots and pans in the kitchen.

I was not more than two years old, and was probably just learning to talk. I began saying the word: “Guitar, guitar, guitar” again and again like a mantra, until the word spiraled into a kind of senseless oblivion, with no relation at all to the object. In wonder at this, I tried the same thing with my name. “Georgi, Georgi, Georgi.” Suddenly I became strange to myself. I was not me. Rapidly, I became conscious of consciousness, and conscious of that. Pure unidentified consciousness, utterly irrespective to body, bed and parent downstairs. I tried it with my mother “Mummy, mummy, mummy.” She also spiraled out of form. She was not who I thought she was. All was consciousness – a kind of brilliant and familiar, greater home. And then I was gone. I don’t remember where.

These sporadic awakenings would continue throughout my time here – these visits to consciousness beyond time. They could be so frequent in childhood years that a deep curiosity surfaced as to where I had vanished in those strange spells, when I wasn’t conscious in this way – when days, weeks and sometimes months passed by. Where had I been?

For decades, I assumed everyone else shared these experiences. It is still hard to believe that they don’t.

Later, a persona developed as a child of “cool” parents, the sister of my brother. Our father, who was a frustrated actor, rising high in the world of marketing, and our mother who too young to be a mother and was frustrated and deeply alone.

I remember screaming rows between my parents in the middle of the night and many domestic dramas, scattered between the ‘seventies parties and the first exposure to school. I recall using the pretext of taking a taste of my father’s beer when he came home after bed-time in order to get to see him. I recall my brother urging me on to go into the living room to stop them fighting, and paying a price for that. Many times, I left home and had nowhere to go and so came back and hid.

My father had black hair and mustache. We used to joke at him that he looked like Hitler. One of my first memories is climbing on him with some urgency and asking “Where’s the war? What’s happening with the war?” I was told that the war with Germany was long over and I could hardly believe it. It was like stepping back through the magical wardrobe into Narnia and finding that decades had passed since five minutes before.

To compensate, my father shared that there were wars and outrages going on. At that time, Iran was fighting Iraq and the horrors of Kurdish refugees gassed by chemical weapons were on the evening news. I took it in. There was still some kind of outrage to be countered here. With the power-cuts of 1973 and by firelight as we munched roasted chestnuts, he also told us about world oil supplies, and what was going on with Israel and the Yom Kippur War.

Some years later, my parents divorced. I was no longer the cool kid of the cool parents, but was now a child of divorce, in a small but cozy housing estate, ashamed, afraid, and smiling through the layers of sexual fear that seemed to surround us.

A few years later, this person, child of divorce, was reformed as one of the ex-patriot middle-class set of Brussels. My new stepfather Jim gave us a new personality, a new class and a new identity. England no longer held us. Nor did the past. The past was left to simmer on the inside of us.

To the English I was Belgian and to the Belgians, I was English. Identity was liberated to lash around unconstrained in the gap between.

During the childhood years I coerced my mother into letting me to joining her for evening classes at the School of Philosophy. This trilingual, international venture was a branch of the School of Economic Science in London. It was an organization that dressed Advaita in a middle-class robe and recruited members out of their own curiosity to find answers to who we are, and why we are here. Advanced courses involved sounding, learning Sanskrit and initiation into transcendental meditation. The School was a hybrid of spirituality and its name has been smeared as a power-focused, middle-class cult (quite rightly, according to my experience) since then. However, thanks to them, the conceptual faculty of mind found form early, with meditation and contemplation on “The Absolute”.

During the childhood years I coerced my mother into letting me to joining her for evening classes at the School of Philosophy. This trilingual, international venture was a branch of the School of Economic Science in London. It was an organization that dressed Advaita in a middle-class robe and recruited members out of their own curiosity to find answers to who we are, and why we are here. Advanced courses involved sounding, learning Sanskrit and initiation into transcendental meditation. The School was a hybrid of spirituality and its name has been smeared as a power-focused, middle-class cult (quite rightly, according to my experience) since then. However, thanks to them, the conceptual faculty of mind found form early, with meditation and contemplation on “The Absolute”.

So in the day time I would go to the campus of the trendy, loosely-disciplined, British School of Brussels with international schoolmates who were the children of diplomates, global businessmen and other internationals that found themselves placed in Brussels, and in the evenings I would be attending groups, serving drinks or meditating at the School of Philosophy. The latter involved having a hair-style that displayed the forehead, a blank face (that’s the face you pull when you’re disentangled from entanglements) and wearing a long skirt. The former, ripped jeans, a cosmopolitan attitude, and the latest fashion. I glided between the two personas and let others make sense of it. The School of Philosophy had me slated as some kind of spiritual star child, which was kind of flattering for one who had no idea who she was, and also resonated somewhere deep down as right and rubbish at the same time.

When I was fourteen, on holiday in the UK with our cousins, my father suddenly died. Catapulted into life and through the rat race of marketing international businesses such as General Foods and K-tel Records, his alcoholism had accelerated and his health deteriorated. The last time I saw him he was a rake, hauntingly foreign and irrevocably part of my own flesh. I found myself again in him, and with saying good bye, found my world ripped in two. Who was I then?

The horror of witnessing his condition led to a deep depression and a despair around the idea that I had to somehow save him, to heal him of his addictions and to bring light into his life. I had tried when he met, on that trembling summer day in the gardens of Blenheim Palace, and failed. Partly because the words I spoke were arising out of the concepts, language and indoctrination of the School of Philosophy. I was talking about the Absolute and meditation, when what I really needed to say was: “You bastard, where have you been? I need you. I love you.”

Chances were lost and the meeting left us both broken inside. When I heard he had died, after a protracted flu led to pneumonia, hospitalization and septicemia, my first feeling was relief. Just a feeling. I had no idea how this death would be a base note of future personas. The relief turned to grief, which turned to shock, which spun back to grief, longing and suicidal impulses. Somewhere between this, was born the idea that his death made me special. My personality began to be crowned by this jewel of norm-busting biography – the horror of my father’s death – as if it made me special, unreachable, unique, wiser, more worthy. It was a given escape from conformity, the simple pain of teenage rejection and not belonging. It was the great “Because” that made me special, a ticket to greater maturity and depth than my teenage peers. The loss gave me a sense of belonging in non-belonging.

In the parallel world of the School of Philosophy, it didn’t go well. These were the ones that had prevented a sequel to the last visit, acting out of a desire to protect me. They stood like pillars of condemning ice in the face of raw human grief, fragility and breakage. A teacher who had played a part facilitating the last meeting with my father at Waterperry House – the schools retreat center in Oxfordshire – approached me post-funeral on the stairway at the School in Brussels. “I’m so sorry to hear about your father’s death,” she said, insecurely, adding: “but it’s only his body that’s dead.”

The childhood bond with the School and all it represented fractured in that moment. The lie of it resounded through many of the other, heartless lies, echoing through the whole of me with the chiming discords of hypocrisy and meeting a defiant heart. The loyalty to this School and to these teachers was forever broken. Within a few years, I would leave the school without looking back, throwing with it a lot of belief and trust in spirituality. Hypocrisy can be a vile tonic that works well to burn the veils of pretense to expose the palpitating, evolving truth of experience in any moment.

I now had a new persona. English child of divorced parents; grief-stricken, nascent poet; living in Belgium with new family; esoterically spiritual; with father now dead.

But who was I? Was I the same one that lived before in England? Was I the same one, who as a little girl rhythmically awakened to the strange miracle of being here, alive, in a body which somehow grew and maintained itself? Could this one die? How would this one die? Where was my father? Where are the dead?

I spent hours a day closed in a room at alone. The death of my father meant little in the Brussels community as no one knew him. It was as if it never happened. I listened endlessly to classical music, inquiring into death, mortality and life. Weeping it out, resting in a kind of stunned shock, and weeping more.

This period climaxed when I decided to commit suicide. I wasn’t sure I would actually do it. As a little child, during the horrors prior to my parent’s separation, I used to fantasize that a small camera was invisibly positioned behind me, up high on the wall – and that the drama of my life was being recorded to be watched on TV elsewhere. In this, I became the actress, standing in front of the front door of the house, waiting for Daddy to come home, and weeping because I knew he would come no more. Now, in this suicidal moment, the camera was also there. I wasn’t so much in the act of committing suicide as in a curiosity-driven ‘enactment’ of suicide.

As such, the tools of the act were not really planned well. I went to the kitchen and took the sharp knife that we were warned was very, very sharp. I took it back to my little hermitage and placed in on my wrist, sensing the sharp preminiscent pain of the blade on the flesh, and waited.

With a shock, I felt myself alive, so incredibly alive. I felt this life as a continuum, and strangely, it translated rapidly into pure logic. That which is ‘A’ can never become NOT ‘A’. What is can never, ever become what isn’t. The line cannot be passed. Suicide would not take “me” away.

What for others could be an exhilarating spiritual experience, was for me a kind of disaster.

I wept and wept, the grief throbbing through the whole body in this choice-less abandonment to life. I wept because there was no way out. I wept because there is no peace in death that is not here in life. I clutched myself in a kind of horror on the realization that death doesn’t happen. Its promise of relief is a very, very bitter trick.

Through all the personas that would follow, this insight never left, and I have never considered suicide since. Suicide is simply not what it deceives us into thinking.

There is a sublime beauty in writing these first ramblings of life story. With each persona written, I die to myself again. I read the words, recognize the events, but from a remote place. None of these personas say anything at all about who I am and who you are. In this timeless moment, where author and reader are one, nothing defines us. We are blissfully free.